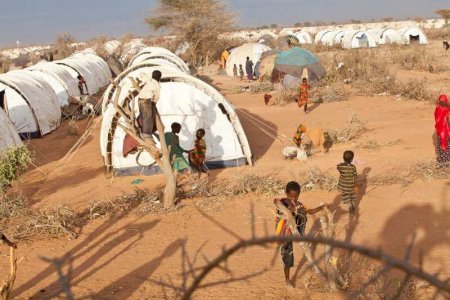

The Kenyan government has again issued an ultimatum to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) to provide a plan and timeline for closing the Dadaab and Kakuma refugee camps. Though the government has issued these demands before, its new ultimatum has caused anxiety for more than 400,000 Somali, South Sudanese, Congolese, and other refugees, many of whom have never known life outside these camps.

When the Kenyan government announced the closure of Dadaab in 2016, it put heightened pressure on Somali refugees to sign up for cash-incentive “voluntary repatriation” by threatening to dump them back empty-handed in Somalia if they missed the deadline.

As journalist Ty McCormick recounts in the newly published Beyond the Sand and Sea: One Family’s Quest for a Country to Call Home, life in the Kenyan refugee camps can feel like a hopeless trap with restrictions on free movement, food rationing, and limited educational opportunities. While the book focuses on one man who escaped Dadaab with a Princeton University scholarship, it makes clear that most people in the camps are “permanent exiles facing a lifetime in waiting.”

But sending refugees to a “home” many have never seen is no solution when conditions there have not improved. As journalist Moulid Hujali, himself a Somali refugee raised in Dadaab, said in a recent podcast, some of those who have signed up for voluntary repatriation because of pressures and conditions in Dadaab have ended up in camps for the internally displaced within Somalia with fewer resources and where the security situation is more dangerous.

On April 8, Kenya’s high court ordered a temporary stay of the government’s ultimatum, which buys the UNHCR about a month to respond. But in the midst of a political crisis, conditions in Somalia will look no better one month down the road.

UNHCR has no quick fix to offer consistent with its protection mandate. Of course, many refugees would like to go home, indeed anywhere but these remote camps, but declaring the problem solved and threatening to truck people to the border is not a solution; it’s a recipe for further dislocation and suffering.

Until the situation in Somalia stabilizes, Kenya needs to maintain asylum and consider allowing refugees at long last to integrate. They could start by opening up, not closing, the camps and allowing those forced to live there freedom to move. Meanwhile, donor governments need to provide financial support and resettlement opportunities that can keep a glimmer of hope alive for those living in the camps.

Source: HRW